Rethinking Interstates Within Neighborhoods

By Eric Hoke, Design Director and Veronica Foster, Communications Manager

10 min read - With the Jefferson Street Highway Cap being discussed within the Mayor’s Office, it is critical to review why highways are being removed and capped nationwide. The blog shares history, visioning, and prompts questions around the next steps for reviewing urban interstates in Nashville. Ultimately, the goal is to share a community’s vision for more pedestrian-oriented transportation systems.

The Plan of Nashville gave people a dream: what if highways could be removed from the Inner Loop?

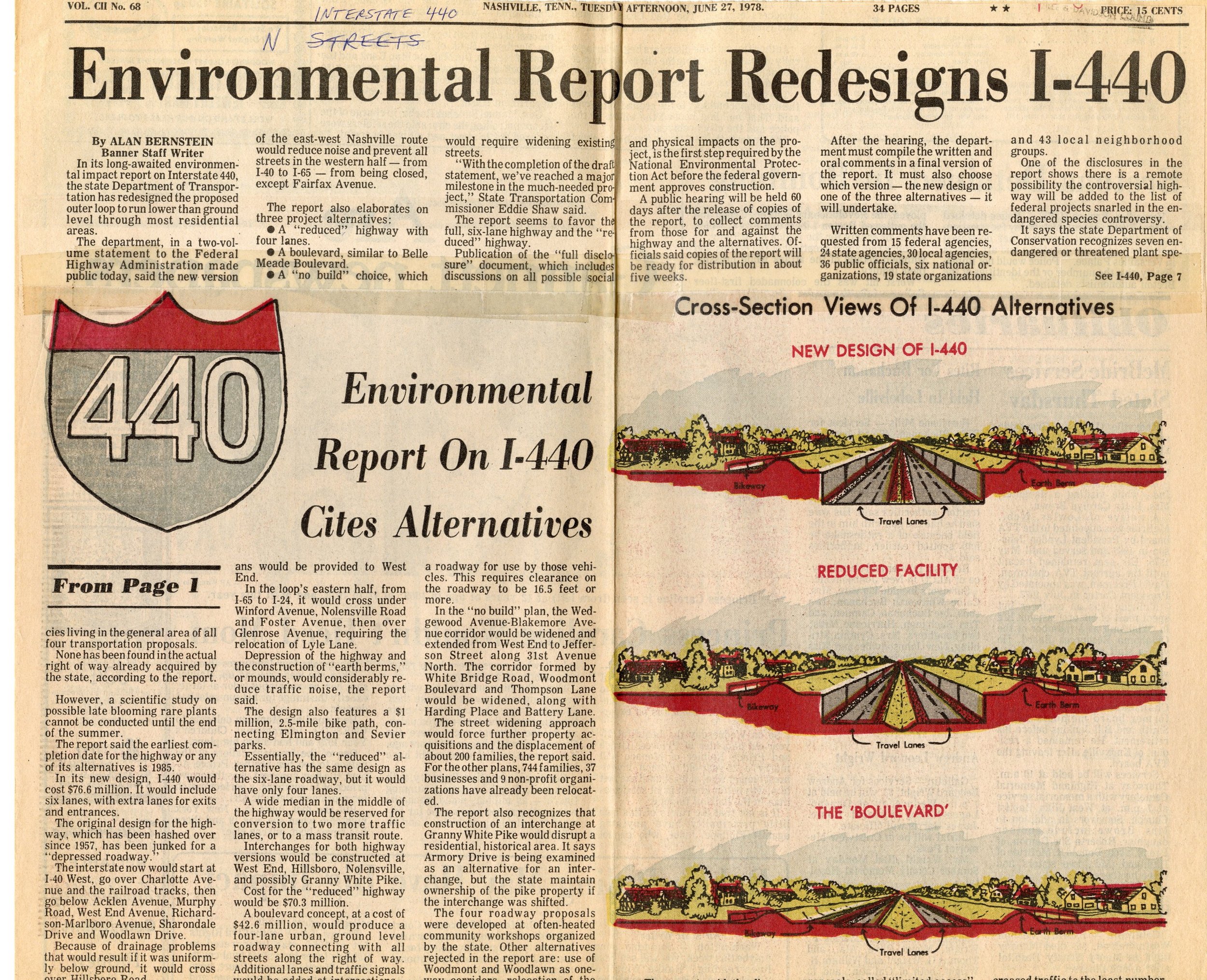

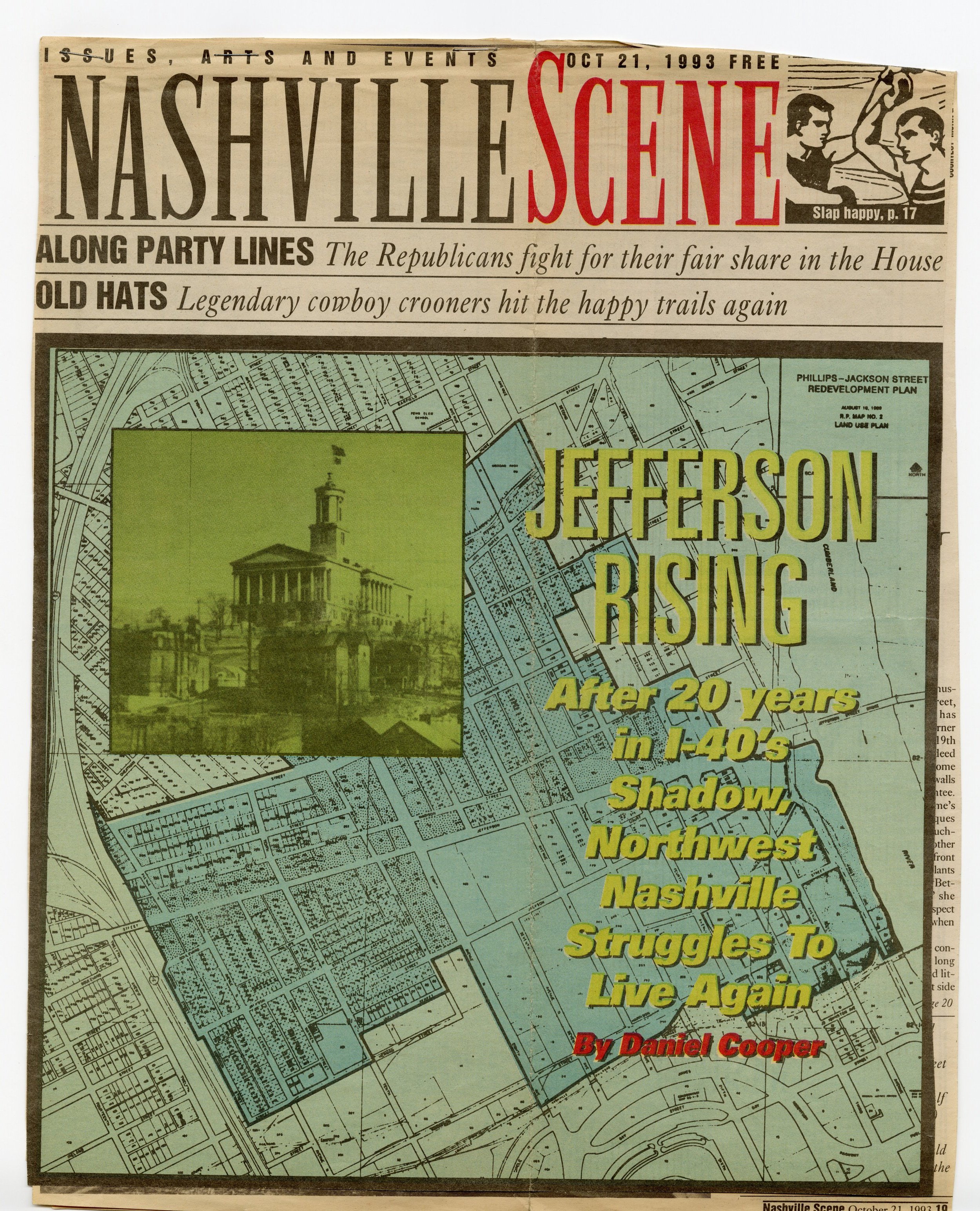

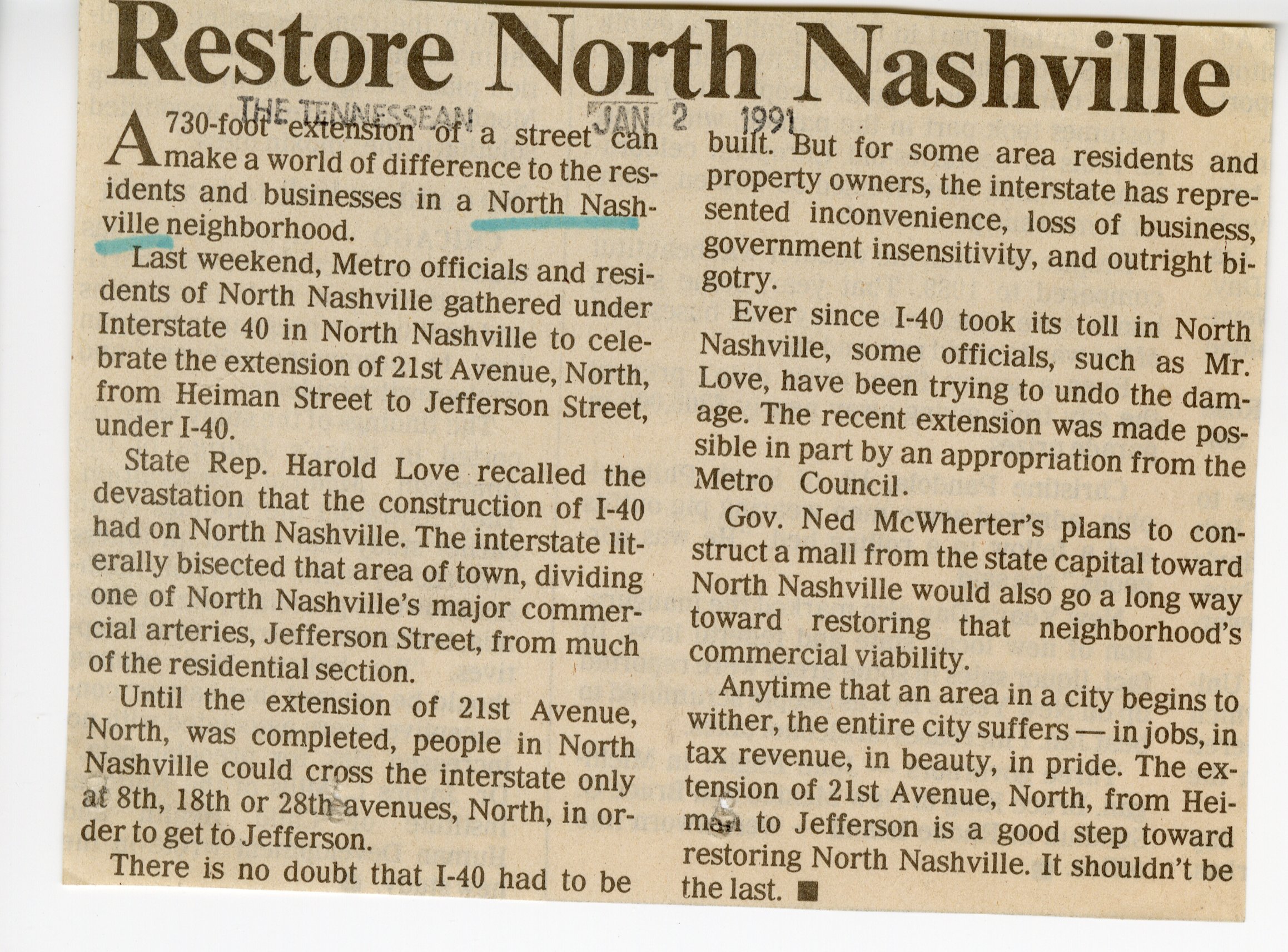

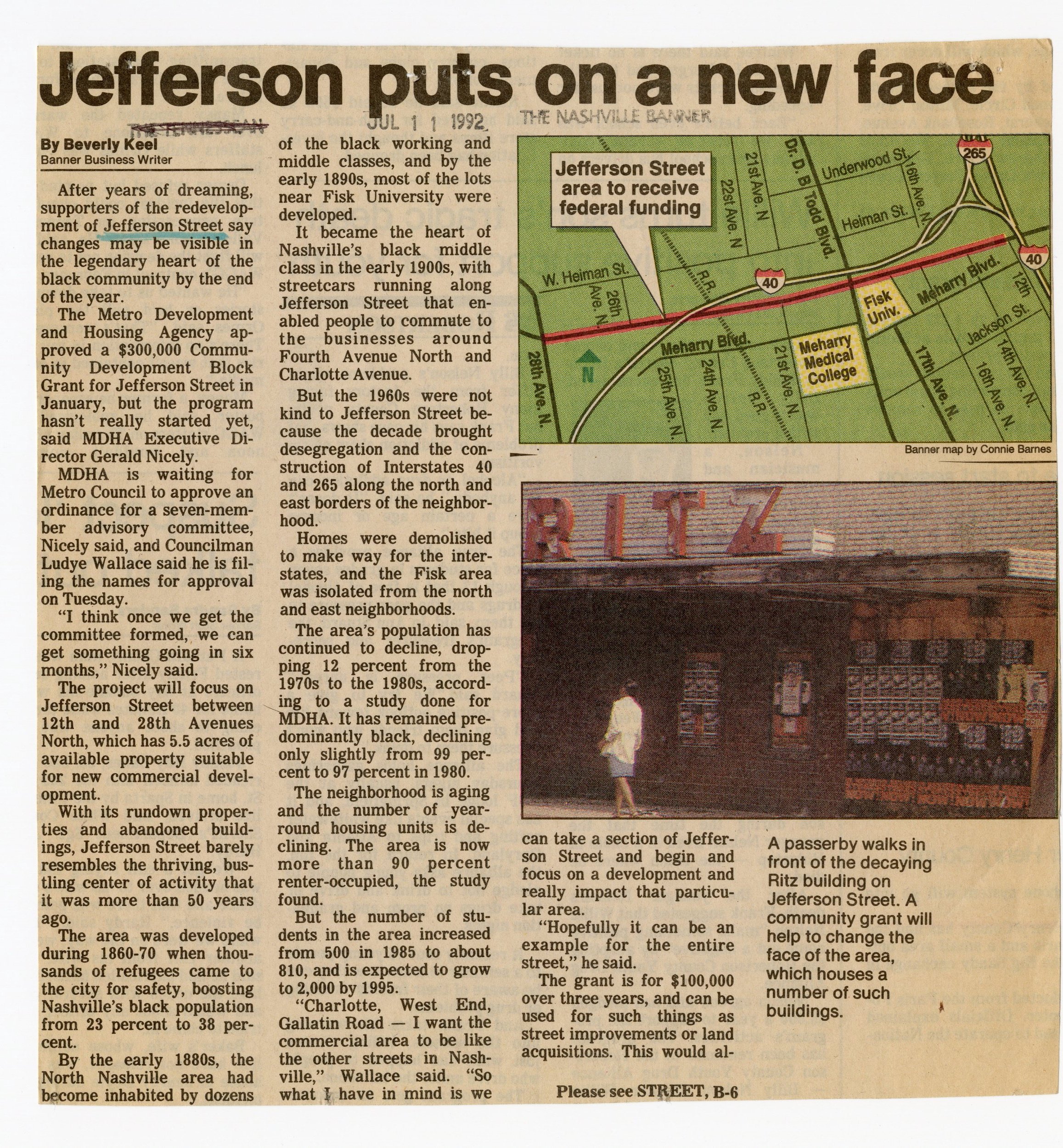

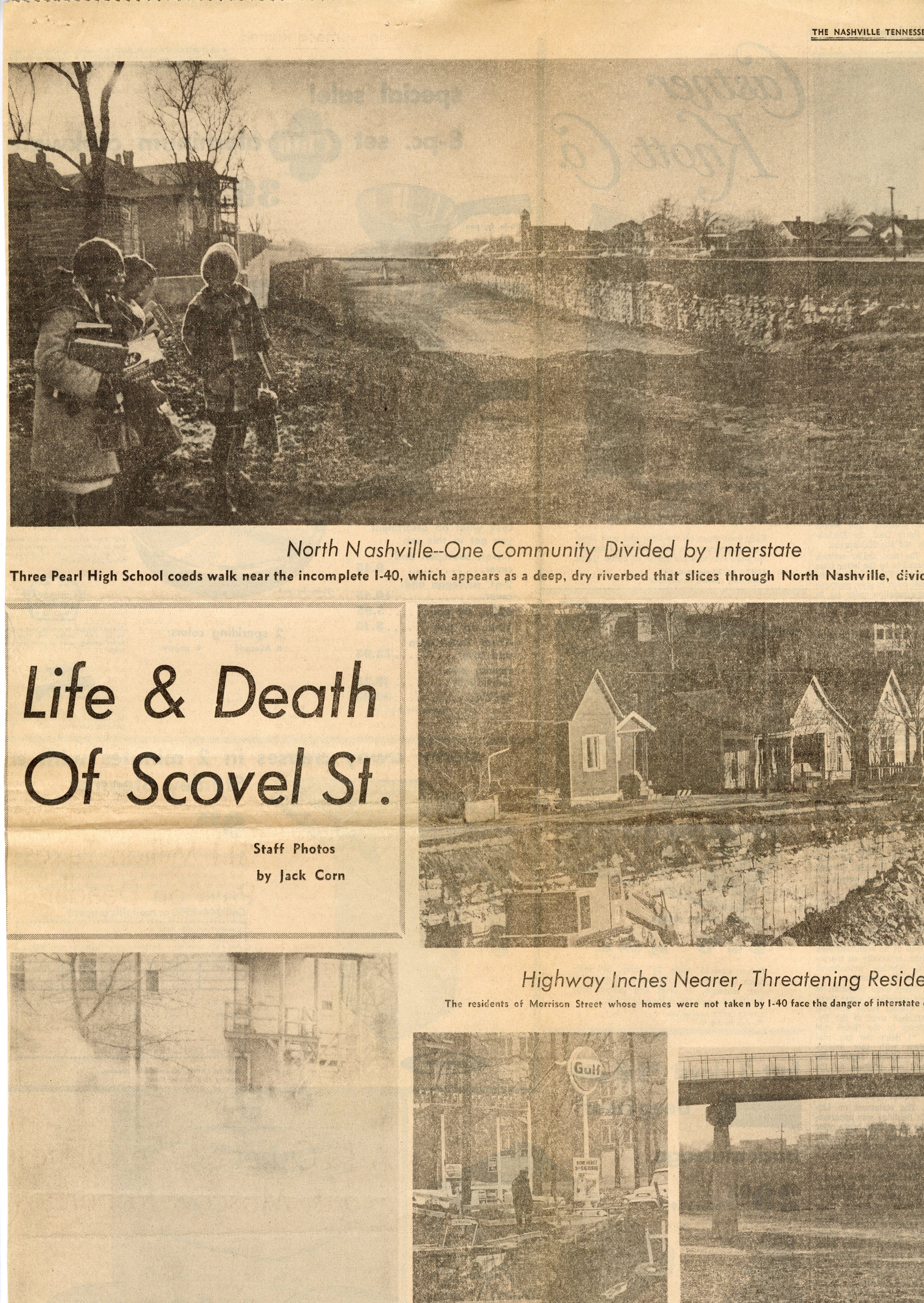

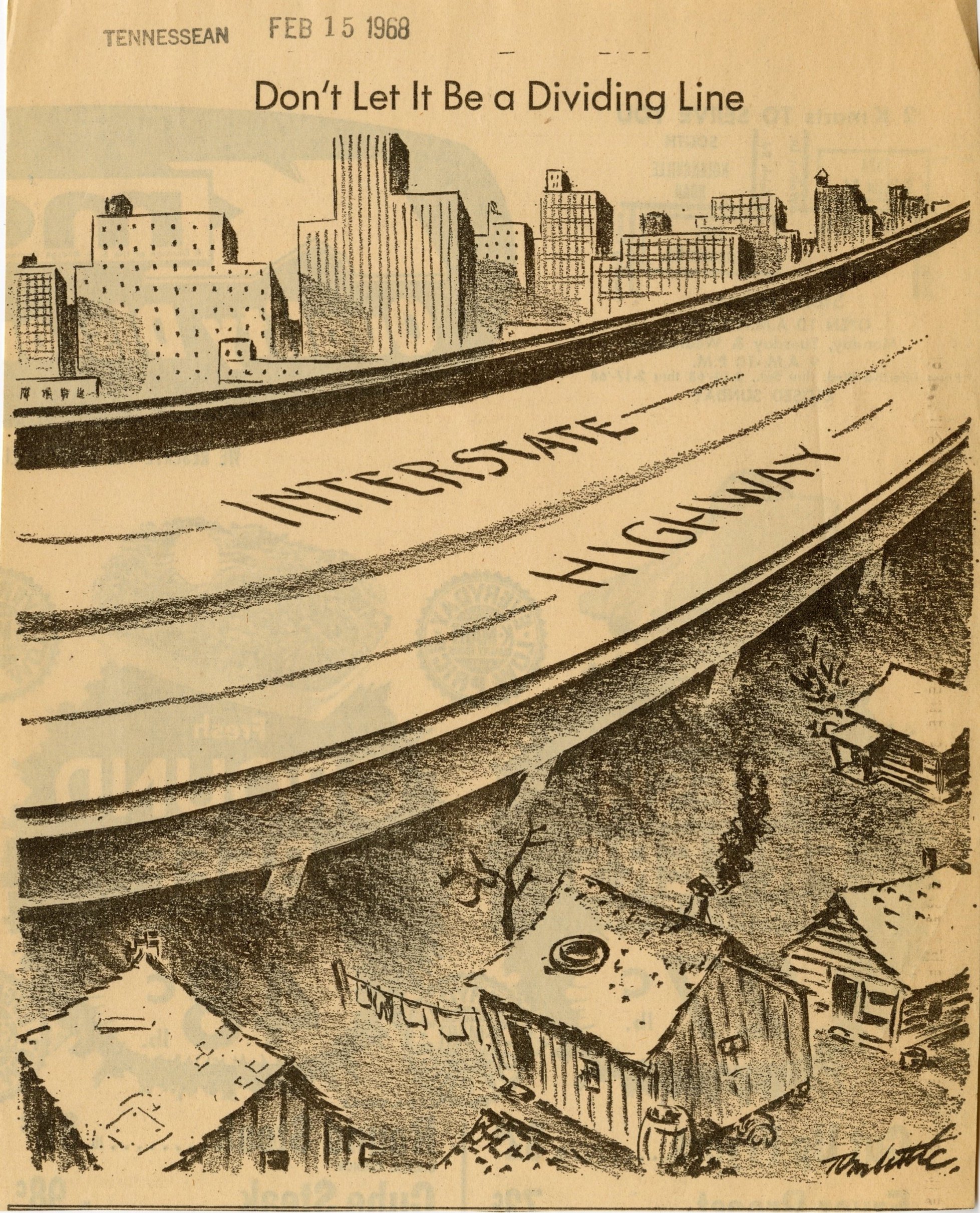

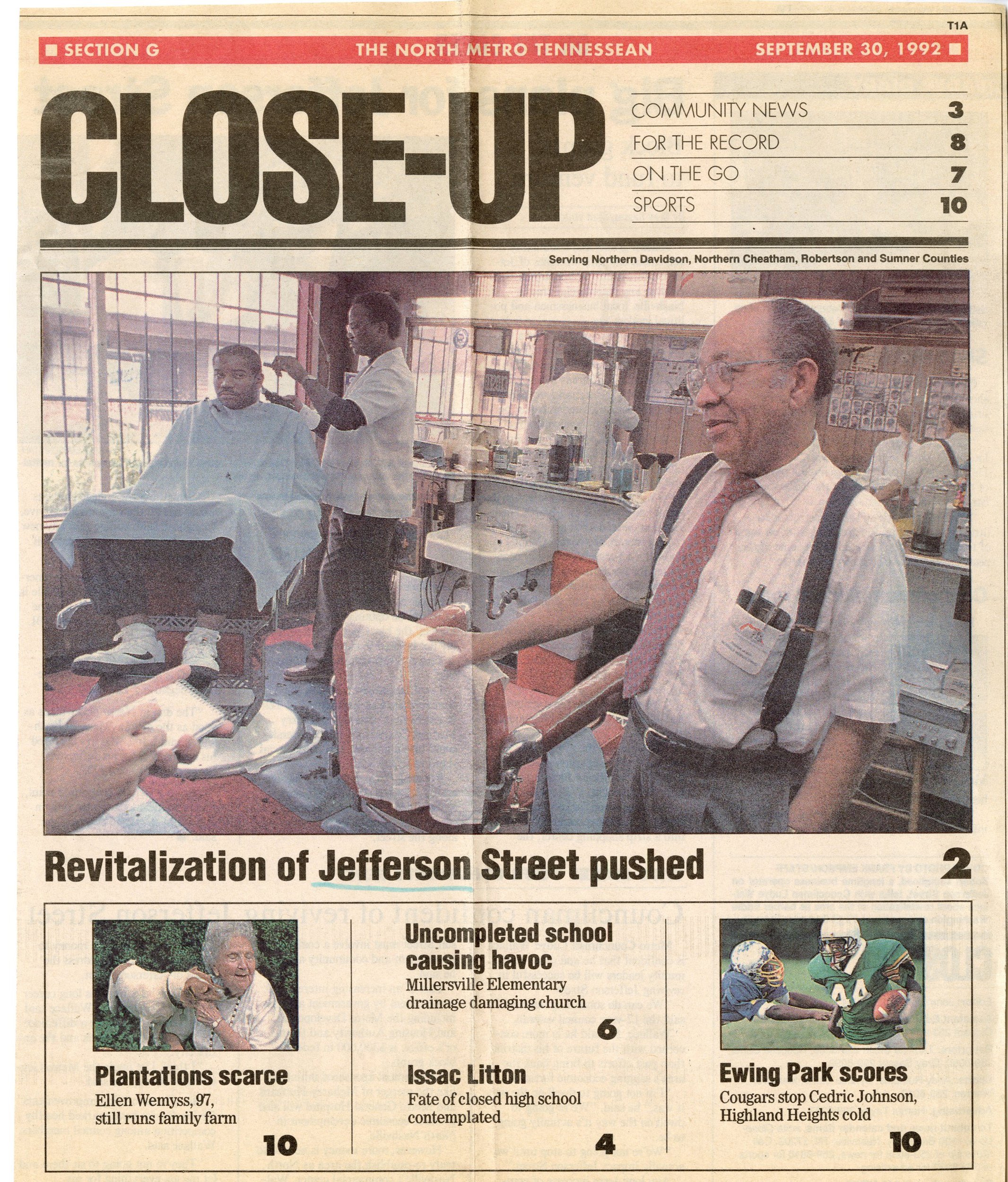

Ever imagined the possibility of removing sections of interstate that would transform into pedestrian-friendly streets? After the disaster of urban renewal, cities all over the country have been dealing with the fallout from major interstate projects. Communities were destroyed or torn apart, neighborhoods cut off from waterfronts, and walkability became unthinkable due to the subterranean and elevated interstates built in the mid-20th century. Highways built through neighborhoods were often a product of systemic racism. Newspapers have been printing articles for years calling on the revitalization of Jefferson Street in North Nashville not long after the section of I-40 and I-65 negitvely impacted the largest Black-owned business community in the city.

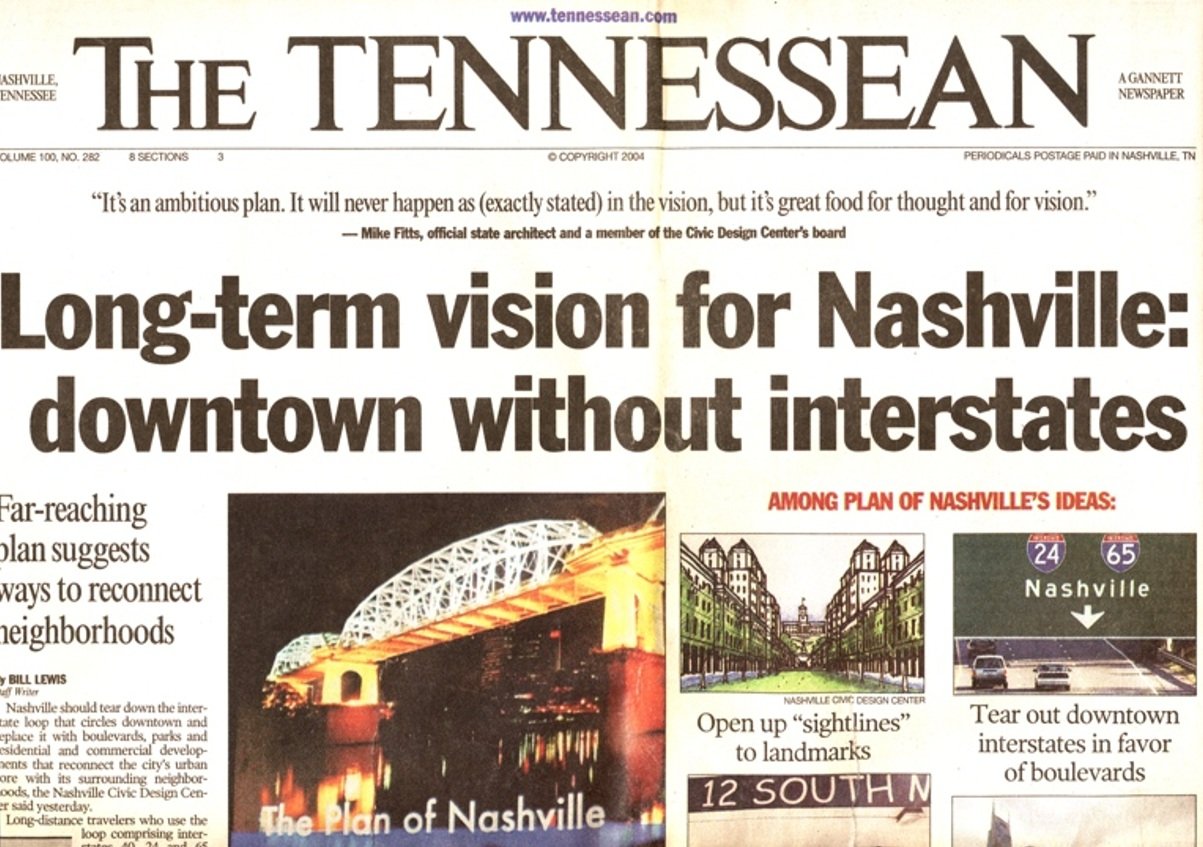

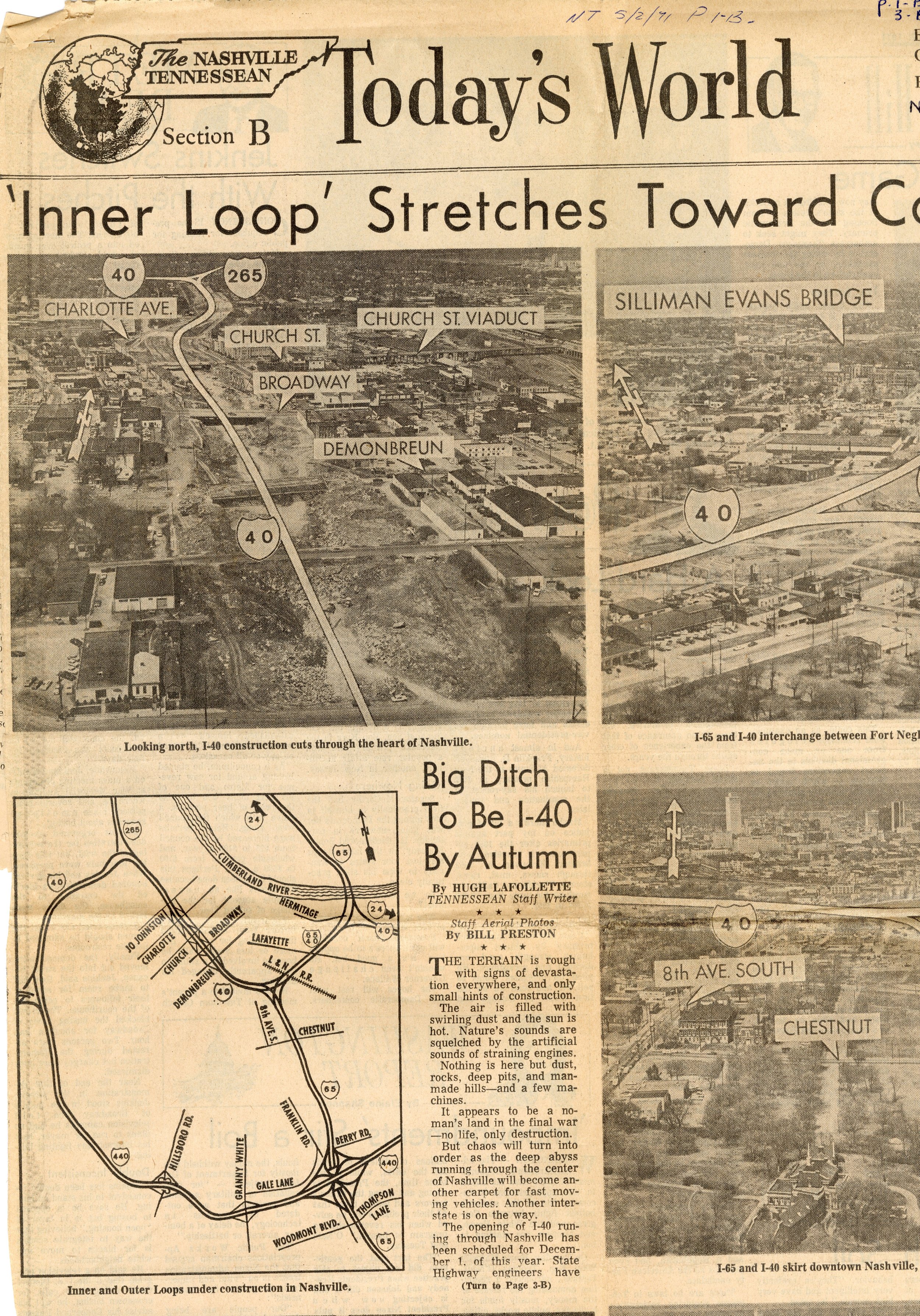

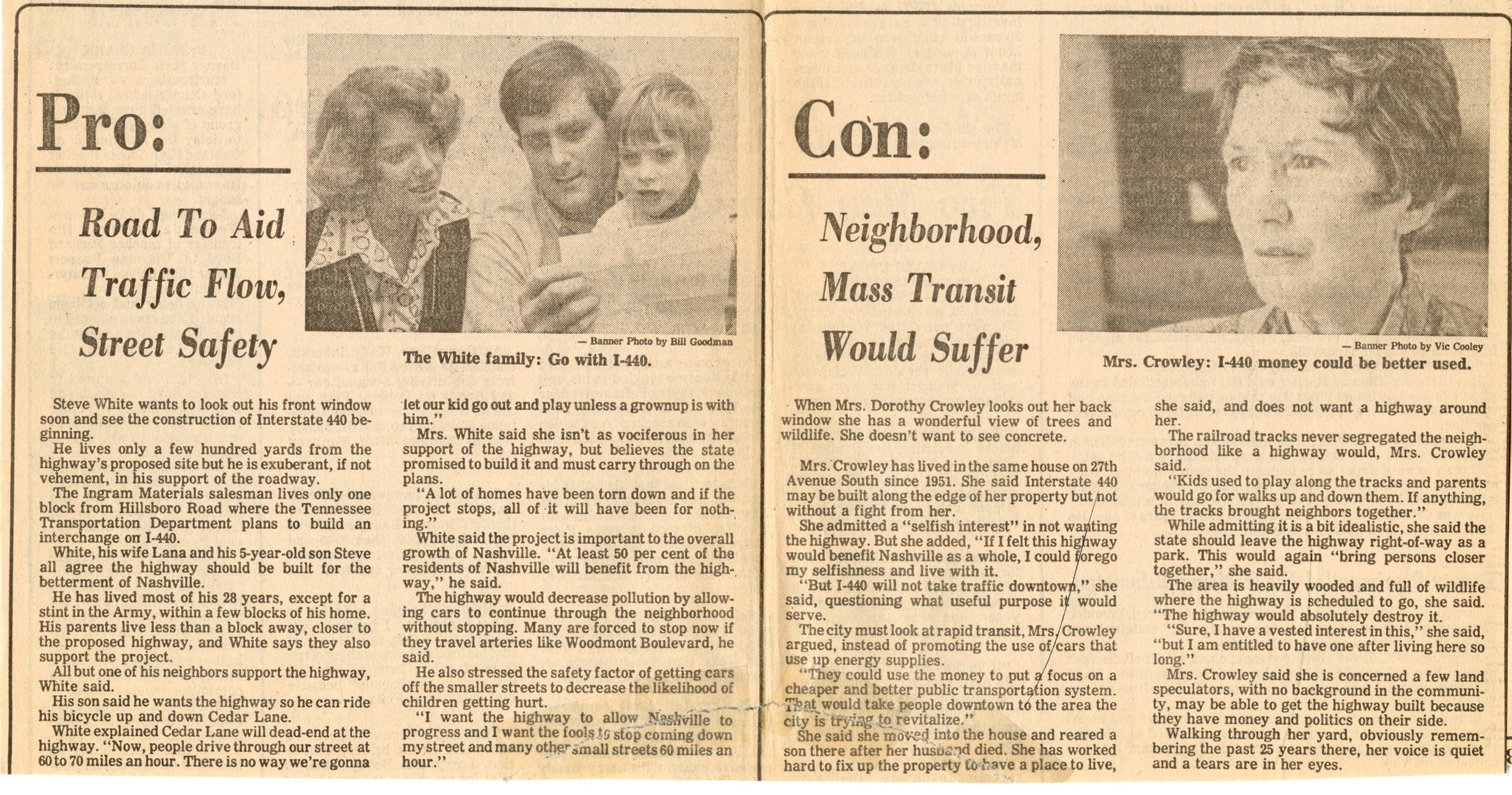

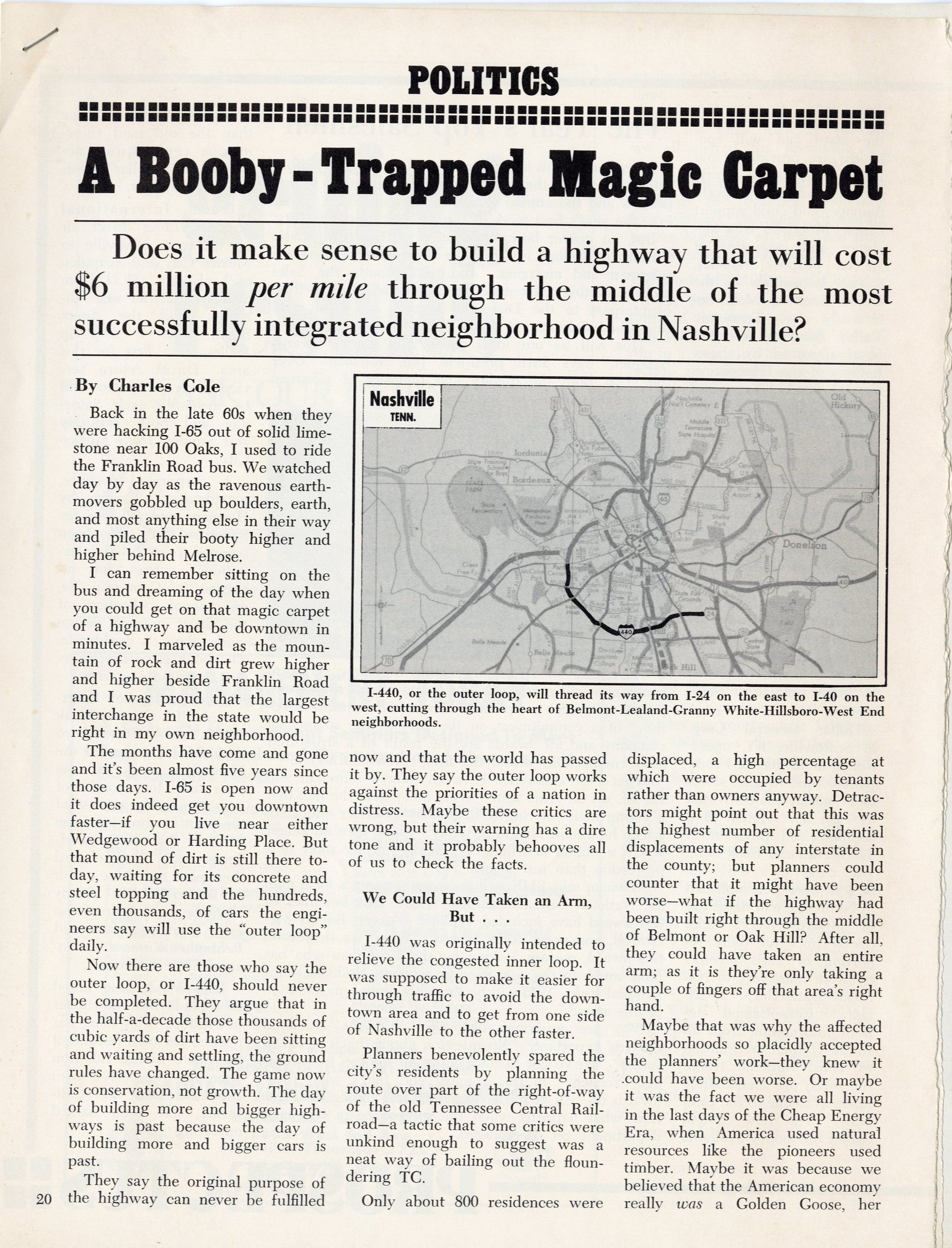

A collection of articles since the 1960s discussing the debate around Inner Loop highway creation and the resulting consequences [Courtesy of the Metro Public Library Archives]

History of the Highway impact in North Nashville

“In 1955, Nashville planned the construction of an interstate system through Nashville, jumping to take advantage of federal funds to accommodate increasing traffic. A preliminary study routed the highway parallel to Charlotte Avenue, but the final recommendation placed it in its present location, through North Nashville along Jefferson Street. In 1967, the I-40 Steering Committee, an organization comprised of African American residents affected by the proposed plan, selected Avon Williams Jr. as counsel and sued the state in the US District Court for a lack of public hearings and alleging racial discrimination in the choice of the highway’s path. Not only would the interstate destroy businesses and homes but it would bisect the remaining community.

Lowell Bridwell, the Federal Highway Administrator, told the steering committee in 1968 that the initial route was changed was due to adverse effects on business, residents, and a hospital, nearly all of which were white owned and operated. In reality, the final route affected a far greater number of residents and businesses than the preliminary. Twice as many homes and three times the number of businesses, apartments, and churches were at risk with the updated plan. The approximately 128 businesses demolished or relocated constituted nearly 80 percent of Nashville’s African American proprietorships.

The court case ultimately failed, as the district court and Court of Appeals both sided with the defense, and the Supreme Court refused to hear the case.”

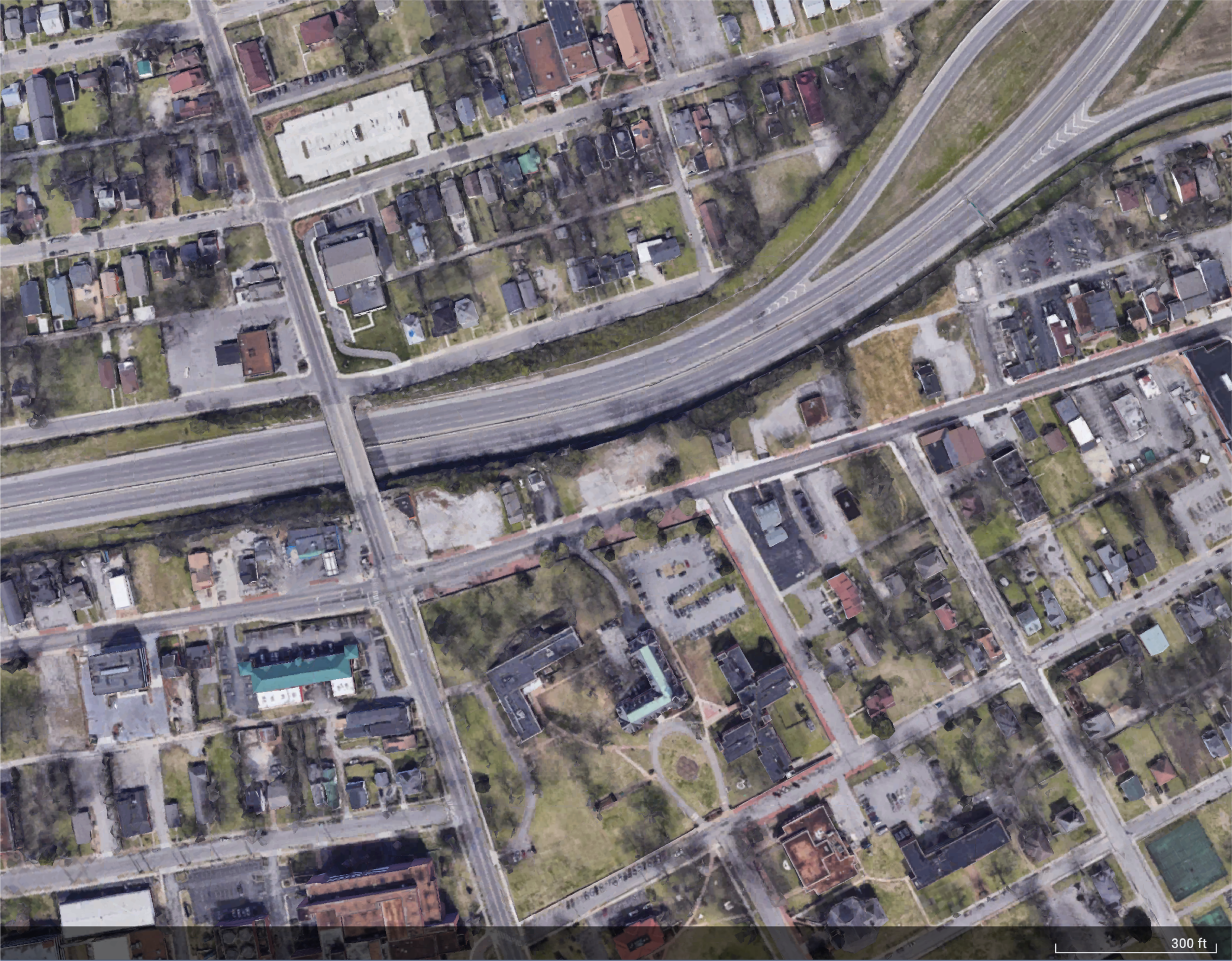

The image above shows the sections of North Nashville where interstate removal was recommended and the historic grid be restored. 6% of Plan Of Nashville process participants favored retaining the inner loop highway segments as it currently existed [Page 76 - Plan Of Nashville]

These images shows how the network could be reconfigured to restore the historic street grid better connecting to North Nashville Neighborhoods to Jefferson St (Page 81 - Plan Of Nashville).

The Before and after animation was side-by-side images in the book that were overlaid here to show how the development and street grid could heal the fractured neighborhoods.

See a historic map of pre and post-interstate construction from Tennessee State Library and Archives.

The construction of I-40 and I-65 was devastating to a once musically and economically vibrant neighborhood and left huge divides and gaps in activity along this corridor. As a way to honor that rich history, the Gateway to Heritage project in North Nashville was envisioned by J.U.M.P. and other neighborhood advocates as a placemaking installation that would showcase important icons who were critical to Historic Jefferson Street and help to relink the divided neighborhood. Jefferson Street was intersected twice by the construction of the interstate and runs parallel to it, less than 200 feet away, for over a mile. Just this section of interstate destroyed 1,800 linear feet of active frontage on the street where Gateway to Heritage sits.

View of the Gateway To Heritage placemaking project shortly after its completion in 2012.

What is the solution to highway-created neighborhood fissures?

In May 2021, we welcomed former Mayor of Charlotte and former U.S. Secretary of Transportation, Anthony Foxx, as our keynote speaker for our Urban Design Forum. Now Chief Policy Officer and Senior Advisor to the President and CEO at Lyft, Anthony’s presentation centered around transportation, equity, and American renewal.

He specifically discussed the impact of highways on Black communities all around the United States. “Infrastructure was built with a lot of intention behind it,” Anthony said, “…[Robert Moses] used transportation as a bit of a weapon to undercut some communities. The Bronx-Queens expressway, for example, went out of its way to take down some of the apartment buildings of integrated communities in the New York area. Almost every urban center has a story like this.”

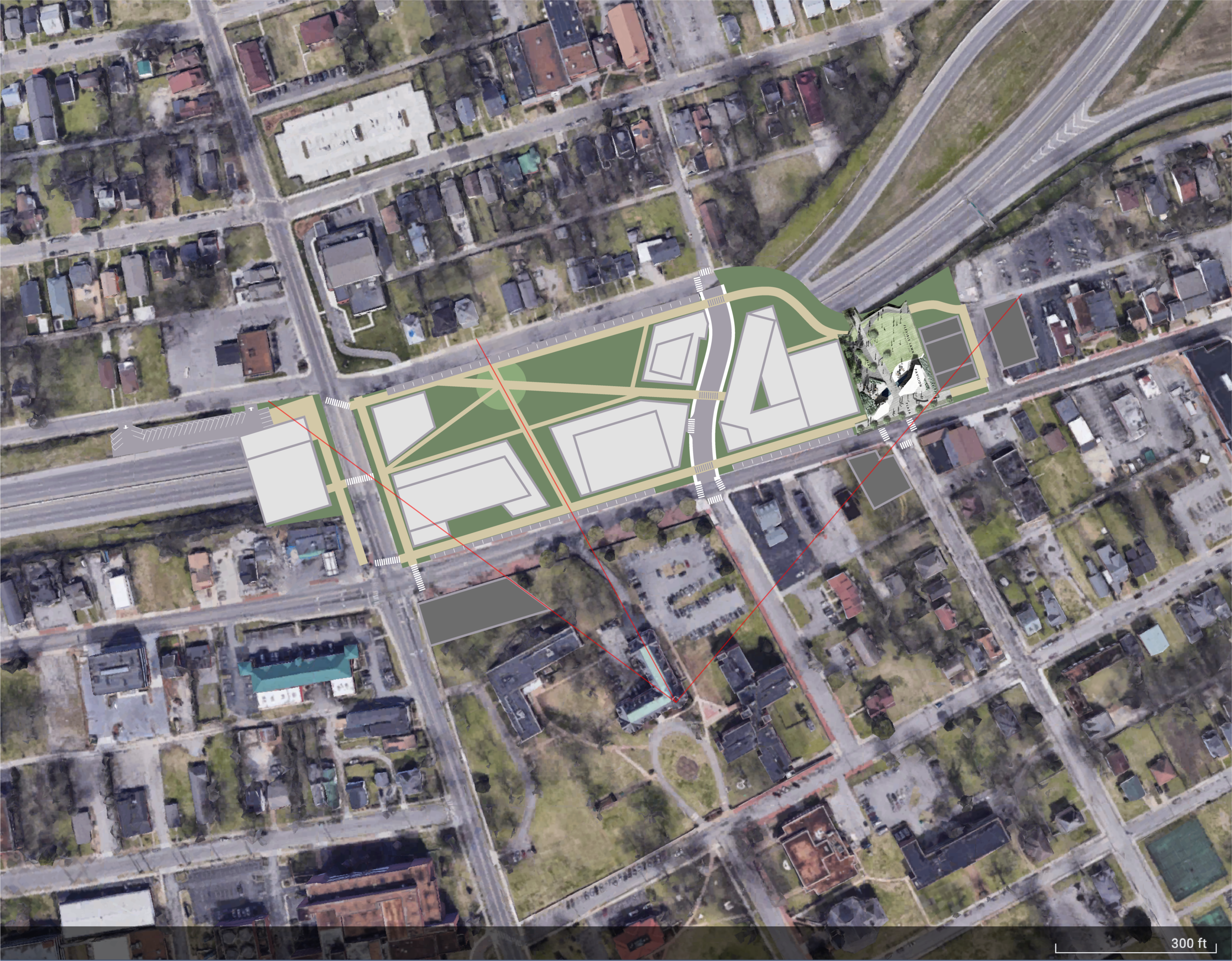

Solid Red: Conversion to urban boulevard, Dashed red: transition from interstate interchange to urban boulevard, Dashed black: removal of interstate and restore historic street grid, Solid black: transition from interstate interchange to street grid, Yellow: interstate configuration stays the same

No matter where you are in the U.S., there is a huge infrastructure disparity in majority white and majority Black neighborhoods. What we can do differently, is to make sure the community affected by a proposed infrastructure project is engaged from the beginning. That is what caused inequity during midcentury urban renewal—a lot of decisions were made prior to the 1965 Voting Rights Act and public input was not sought.

After half a century of navigating the major issues that I-40 and I-65 created in our own city, The Plan of Nashville (2005) proposed the radical idea of removing large sections of interstate to reconnect neighborhoods. Of 800 Nashville community members, 94% of participants in design charettes (or group visioning sessions) were in favor of removing the interstate. The Plan has been a foundation for the Civic Design Center's work since its creation, and we continue to discuss the design visioning that reminds communities about possible steps to undo questionable midcentury planning.

We would like to ask a few questions before you continue reading.

Is highway removal or highway capping a possibility? Are other cities around the United States removing or capping their highways? What are community members’ hopes and fears related to interstate removal and interstate capping? What are other community resources that are needed to sustain and grow communities when influenced by an interstate?

Interstate Capping as Restoration

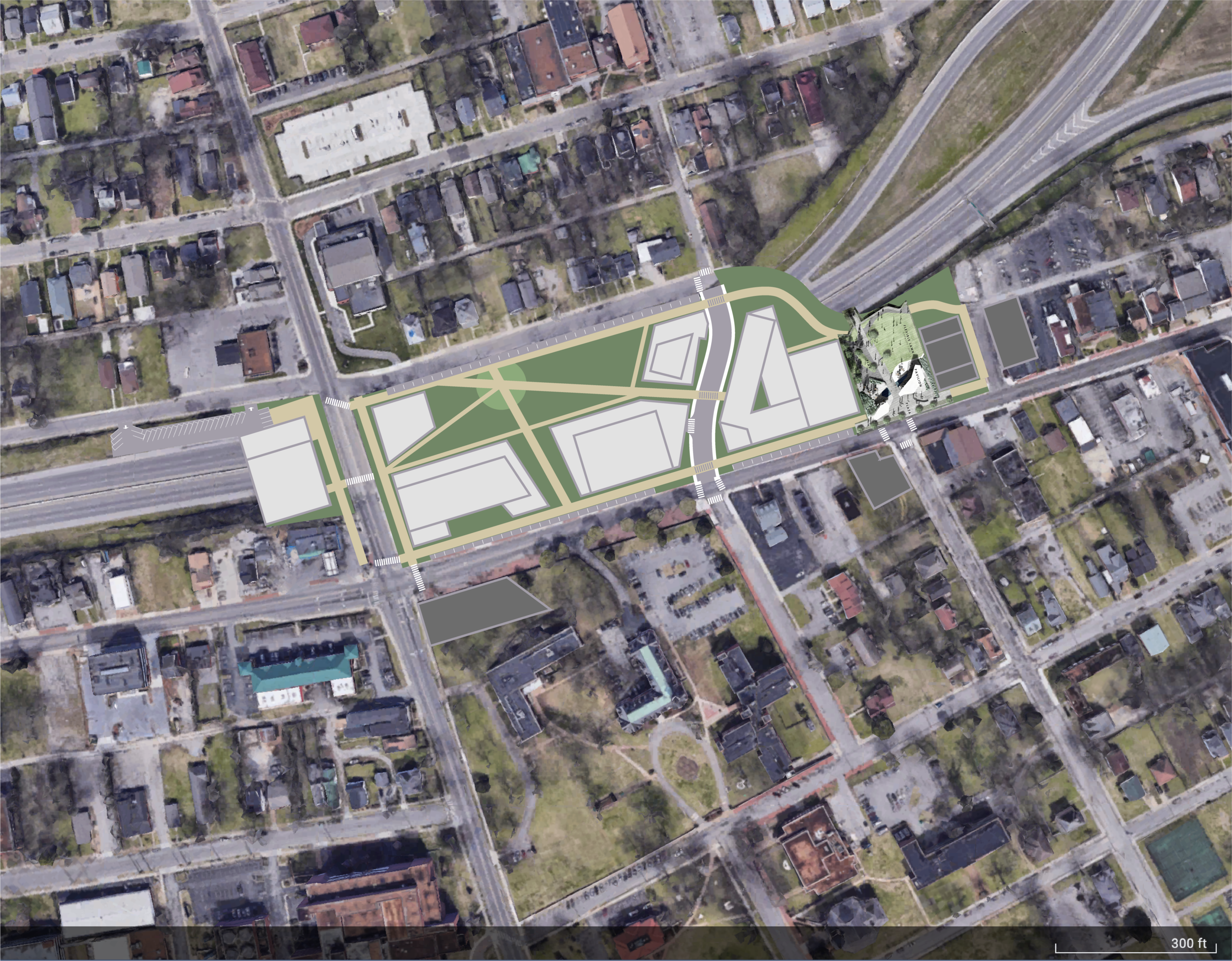

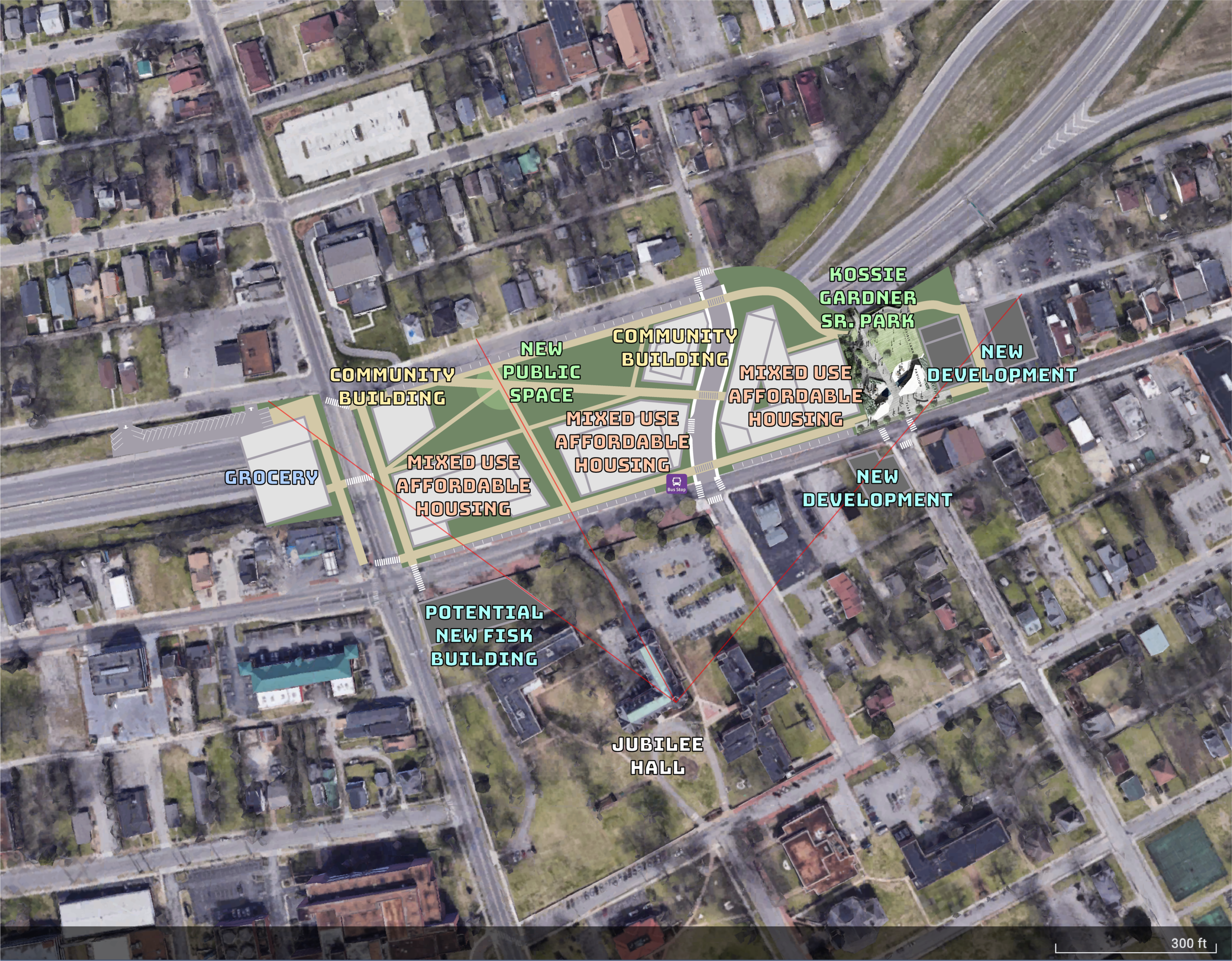

These images show potential for highway caps along the I-65 and I-40 corridors in North Nashville [Page 121 - Shaping The Healthy Community]

The idea of interstate capping was not originally presented as a solution for North Nashville in The Plan Of Nashville. Removing the interstate and replacing it with the historic street network was the radical proposal suggested at this time.

Later when the Civic Design Center published Shaping The Healthy Community (2016) we created diagrams that started to better illustrate how three highway caps in North Nashville could start to implement healing the grid ideas from The Plan Of Nashville. This was also at a time when the concept of highway capping was becoming more prevalent in the US (we looked at examples like Klyde Warren Park in Dallas, Boston's Big Dig Project, and Seattle's Freeway Park). The locations shown in the map below were the most feasible places to imagine highway capping as a solution based on various factors - accessibility, roadway elevation, and impactful economic development.

Jefferson St Capping Project

Buchanan St / Delta Ave Capping Project

Dr. D. B. Todd Blvd Capping Project

The above image shows a before/after idea for the Jefferson St Capping Project over I-65. This could reconnect several east and west streets to adjacent neighborhoods and provide opportunities for new community-centered amenities.

The Summer after Shaping the Healthy Community (SHC) was published, Congress For New Urbanism hosted one of the Every Place Counts Workshops in partnership with Tennessee Department of Transportation and the Mayors’ Office that focused on the D.B. Todd Cap which connected to several properties on Jefferson Street shown in SHC (other areas along Jefferson Street were previously discussed).

A visualization of a Midtown highway cap

In April of 2019, the Civic Design Center worked with the Vanderbilt School of Engineering to look at the feasibility of interstate capping projects. This particular project focused on the section of roadway between Midtown and The Gulch.

At the Civic Design Center’s June 2020 Urban Design Forum - Healing the Grid and Reconnecting Communities we talked with OJB Landscape Architecture about two capping projects they worked on in the Dallas, Texas area. We learned about the exciting designs and challenges these types of infrastructure projects encompass.

A before and after aerial view of Klyde Warren Park highway cap in Dallas, TX

In November 2020, Kossie Gardner Sr. Park opened at the intersection of 17th Ave and Jefferson Street. This pocket park was built on top of a Metro Water project and helped to fulfill a park deficit in North Nashville according to Plan To Play, a guiding document that provides a 10-year vision to sustainably meet community’s needs. In partnership with Metro Parks and HDLA, the Civic Design Center collected feedback that informed the design of this park. Only half of the funding was raised for its construction, but the park is still slated to get an outdoor amphitheater to the east of the 17th Avenue walkway. One of the most successful elements of this park is the Art and History walls that were intentionally placed to the rear of the site bringing attention to the divide that the interstate created in this community.

Entrance to Kossie Gardener Sr Park at 17th Ave N

Playground in foreground and art and history wall that terminates the walkway through the park where the highway carved through the neighborhood

In December of 2020, Mayor's Office representatives presented the Metro Nashville Transportation Plan endorsed by Metro Council. The document showed the Jefferson Street Multimodal Cap/Connector with a price tag of $175M. The Mayor's office asked the Design Center for help to develop renderings that begin to illustrate the D.B. Todd and Jefferson Street cap in slightly more detail.

The intention was to convey the concept for the space and provide community members with a tool to imagine possible solutions for the recessed highway. The following images could help visualize the capping ideas highlighted in the Transportation Plan and help to award grant funds for the project. The Mayor’s Office submitted a grant application that would award $120 million for a Rebuilding America grant to help pay for the cap, but it was denied in March.

Regardless of whether or not community members are interested in a highway cap as a solution, we must consider neighborhood identity, adjacent development, affordable housing, accessibility, and far more before moving forward.

Ariel view looking east of proposed Dr. D. B. Todd Blvd Capping Project. Fisk Universiti’s Jubilee Hall is pictured on the right side of the image with the green roof and cupola.

Existing/proposed perspective view looking east over the interstate from the existing Dr. D. B. Todd Blvd Bridge

Opportunities of Highway Capping

The image below illustrates thoughts on how to incorporate community-centered amenities that could help address the historically devastating decisions to build an interstate through a thriving neighborhood. The highway cap allows for the construction of new buildings that could support affordable housing with active storefronts on Jefferson Street. The facades of these buildings could architecturally pay tribute to the vibrancy and feeling of Historic Jefferson Street. In this area of North Nashville, the closest grocery store is over one mile away. Considering how you may build on top of a cap, the highway gap is over 200 feet wide and could easily accommodate the footprint of the nearest grocery store (positioned on the left edge of the cap idea in the image below).

The physical fissure of the street grid is not the only injustice that occurred with placement of the interstate in North Nashville. There is significant carbon emission from interstates and capping projects could mitigate and control carbon output along freeways to lessen air quality impact from the heavy traffic volume.

One of the most notable buildings in Nashville is Fisk University’s Jubilee Hall which sits just to the south of the proposed cap project. Positioning pathways and buildings to preserve sightlines (a foundational Guiding Principle) to the cupola will feature this landmark to improve wayfinding and civic identity. This project has the potential to restitch parts of the street grid split by the interstate, particularly 16th and 17th Avenue North. These new connections could lead to a new public plaza or park-like space which could be surrounded by community buildings such as music spaces, entrepreneurial incubators, or community centers creating a new nexus for North Nashville.

With new housing, community buildings, streets, walkable connections, and existing transit (such as Route #29 that connects TSU to Downtown), this cap project could emphasize an environmentally sustainable, culturally vibrant, and population-dense neighborhood that could pay respect to neighborhood residents and be a source of civic pride.

Returning to Our Questions

Is highway removal or highway capping a possibility? Absolutely yes.

Are other cities around the United States removing or capping their highways? Yes, and many of the most notable projects have been in areas around Downtown—Boston, Dallas, Seattle, etc. On the other hand, there is ReConnect Rondo in St.Paul, MN, a community-led project working towards a highway cap, or land-bridge, that aims to support the local African American community deeply impacted by I-94.

We ask YOU to answer the next 2 questions regarding the possibilities in North Nashville. Please comment on the blog stating your identifiers (age, race, and neighborhood where you live) if you feel comfortable, so we may start a dialogue about the future of repairing highway-imposed neighborhood fissures in Nashville.

What are community members’ hopes and fears related to interstate removal and interstate capping? What are other community resources that are needed to sustain and grow communities when influenced by an interstate?

Want to learn more about the North Nashville capping proposal?