Green and Complete Streets: Planning Our Roads to Imporve Nashville’s Water Quality

By Catherine Price, Cumberland River Compact

8 min read In early 2025, the Civic Design Center partnered with the Cumberland River Compact to implement a REACH (Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health) initiative funded by the Tennessee Department of Health. Supported by the Center for Disease Control, the REACH grants aim to reduce health disparities and promote chronic disease prevention among populations most at risk.The Bordeaux neighborhood has long faced the impacts of underinvestment in public infrastructure and limited access to green space. These systemic barriers have contributed to significant health disparities and poorer outcomes for residents.

Our partnership brings together expertise in community engagement, urban design, watershed stewardship, and green and complete streets planning to build a network of interconnected, health-promoting assets throughout the neighborhood. By working alongside residents and local stakeholders, we aim to expand access to parks, safe and shaded multimodal routes, and resilient stormwater infrastructure—while honoring Bordeaux’s cultural history and the ecological vitality of the Cumberland watershed. In this blog post, Catherine Price of the Cumberland River Compact explores how Nashville’s existing Green Streets policy can be a tool—when combined with community leadership—to embed health equity into the built environment of Bordeaux.

Learn how Nashville’s road design can catalyze healthy waterways, and how a future Green and Complete Street on West Trinity Lane could take shape.

Photo of 28th Ave Connector east of the OneC1TY Development

It can be a challenge to keep up with all the development in Nashville – many have joked for years that our state bird must be a construction crane. As the Cumberland River basin’s largest city, Nashville’s growth and development have a big impact on water quality.

Criss-crossing the growing city are thousands of miles of roads. If you left your house today, you used a road to drive, walk, bike, or take public transit to your next destination. Street infrastructure is crucial to how residents experience the city. Urban streets don’t often conjure a sustainable, resilient, or green image in most people’s heads. But what if they could?

Nashville deserves a clean and healthy downtown Cumberland River, and our streets can help us get there. Prioritizing green and complete streets alongside the Cumberland River can connect people to the river, promote clean water, and ensure long-term resilience for our city.

In pursuit of this goal, the Cumberland River Compact and the Civic Design Center have partnered to envision how Nashville can implement robust green and complete streets across the city, and have developed a vision for how to turn West Trinity Lane into a model green street. Slated for a wave of new construction along the corridor between Clarksville Pike and Whites Creek Pike, this 2.5 mile stretch of road has the opportunity to serve as a model for green and complete streets throughout Nashville and beyond.

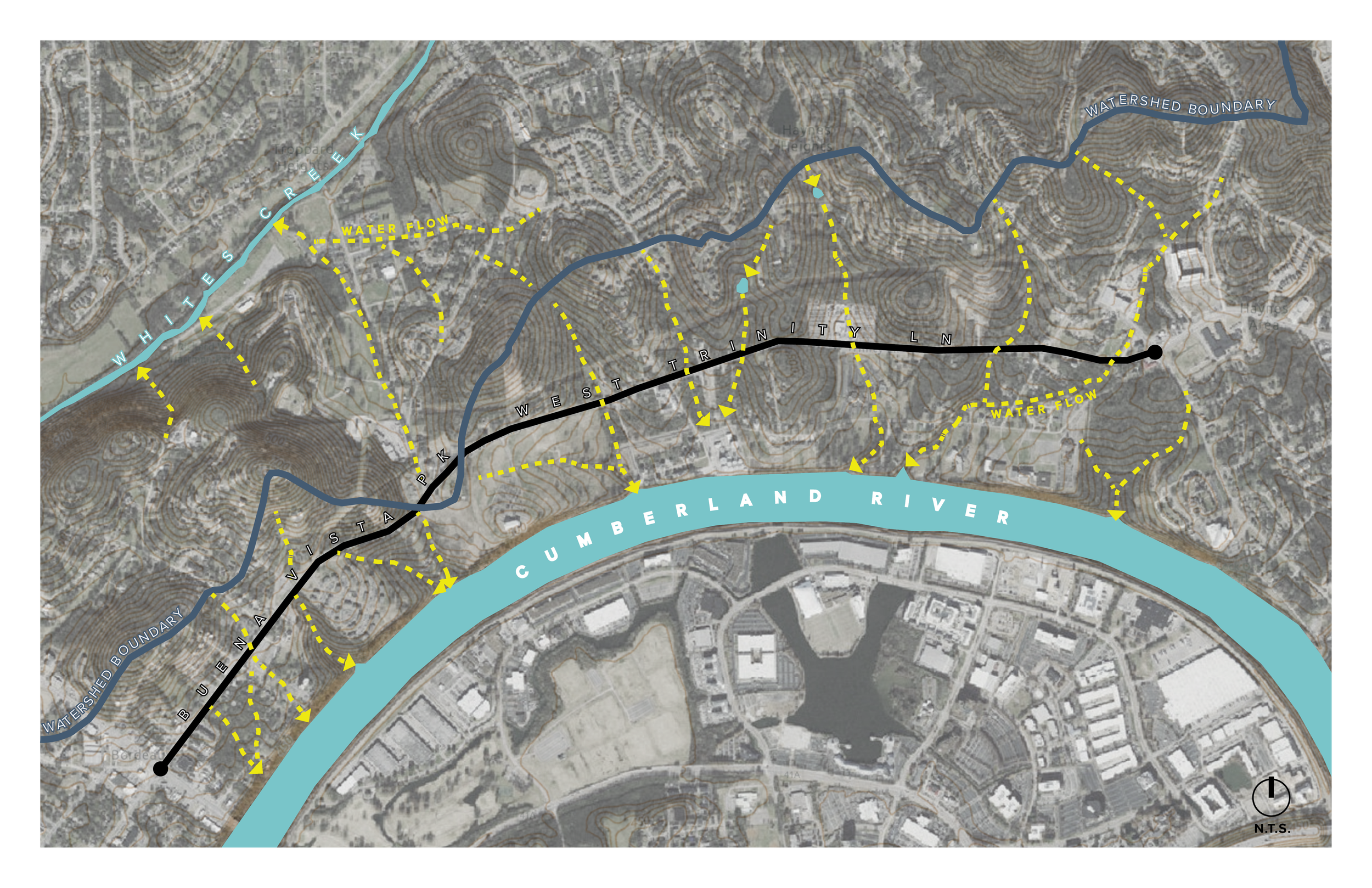

As shown in the watershed/drainage map above, a significant amount of stormwater runoff from West Trinity Lane flows directly into the Cumberland River.

NASHVILLE DESERVES A CLEAN AND HEALTHY DOWNTOWN RIVER

Nashville is lucky to have 55 miles of the Cumberland River flowing through it. Paved surfaces, such as high-quality roadways and sidewalks, are needed not only for cars but also for bus riders, cyclists, and pedestrians. As the city embraces the river in new development, it’s more important than ever to prioritize the construction or modification of green streets along the river. When green stormwater infrastructure (like native plant landscaping and street trees) is included in street designs, they are more aesthetically pleasing, more walkable and bikable. Designs like these also protect one of Nashville’s greatest natural resources – clean and abundant freshwater.

ROADS AND WATER HEALTH

Connecting our roadways to our waterways isn’t new. It’s actually how our city was designed. Nashville was designed as a hub-and-spoke, where major corridors such as Nolensville Pike, Gallatin Pike, and West End Avenue run to downtown Nashville from outlying neighborhoods. This mirrors how our urban waterways tend to run towards the downtown riverfront. For example, Mill Creek has a similar path to Nolensville Pike, and Brown’s Creek runs alongside Franklin Pike.

If you regularly walk, drive, or bike along a road that runs next to a waterway, maybe you’ve seen its water level, color, or current change with different amounts of rain. Maybe you’ve even seen a creek spill out onto a roadway during a severe storm. With sufficient green infrastructure, these waterways can be cleaner and better protected, and flood risk can be reduced.

When it rains, the water runs across paved surfaces like parking lots and roads, picking up pollutants. This rainwater runoff ends up in creeks and streams across the city, and eventually the Cumberland River, our source of drinking water. Stormwater can carry pollutants like dirt, excess fertilizer, dog waste, oil, tire particles, microplastics, and more directly to our water source. Stormwater that flows over hot roads also heats up, and its raised temperature can disturb the sensitive aquatic habitats it enters.

Roads are permanent, impervious spaces. Unlike buildings, which can implement green roofs, bioswales, and rainwater capture to improve stormwater, roads are, by definition, hard surfaces where water cannot soak in. Fortunately, there are solutions that can be built within and around roads that absorb, filter, and slow stormwater runoff, and can address the toxic pollutants and petroleum byproducts that tend to originate from roads.

GREEN STREETS IMPROVE WATER QUALITY AND OUR COMMUNITIES

Diagram showing how the Trinity Lane Green Street treatment can work to help protect and filter storm water before it eventually ends up in the Cumberland River

Green streets incorporate green stormwater infrastructure into their design to help capture, clean, and cool stormwater before it enters nearby streams, and ultimately help to improve water quality. Examples of common green stormwater infrastructure include bioretention basins and bioswales, which are native plant wells that absorb stormwater, and urban trees that help slow down falling rain and help it absorb into the ground.

Metro Nashville’s Green and Complete Streets initiative combines the green infrastructure of green streets with broader transportation goals, such as improving public transit and creating safe corridors for pedestrians and cyclists. It makes sense to tackle these issues in tandem because research has shown that green streets are safer and more equitable for everyone.

The benefits of green streets go beyond just water quality.

Trees planted on streets can improve air quality and reduce asthma rates by absorbing particulate matter in the air.

Green streets can reduce heat exposure when walking or biking by providing shade from trees, cooling the heat-absorbing pavement.

Elements of green streets, like bioswales and trees, can be strategically used to separate car traffic from pedestrians and bikers, providing additional safety and encouragement for active transportation.

Green street elements can reduce car speed by altering a driver’s perception of the road, making it feel narrower and leading drivers to slow down.

Street trees have been shown to increase the longevity of sidewalks and roads. Shade from trees reduces extreme surface temperatures and minimizes surface runoff on asphalt, thereby minimizing deterioration. A street covered by at least 20% shade can reduce repaving costs by 60% over 30 years.

GREEN STREETS IN NASHVILLE

You’ve probably seen a green street in Nashville and may not have known what it is!

28th/31st Avenue Connection -This Green and Complete Street connects North Nashville and West Nashville with traffic lanes, separate bike lanes, and sidewalks. The road is sloped so that stormwater runoff flows into a series of bioretention basins along the street. Listen to Cumberland River Compact Executive Director Mekayle Houghton discuss this project on an episode of Volunteer Gardener.

12th Avenue -The 12th Avenue Green and Complete Street project between Lawrence Avenue and Division Street separates vehicle traffic from bike traffic with a series of bioswales. These bioswales manage stormwater runoff and are filled with native plants.

Madison Station – Tucked behind the Madison Library near Amqui Station, you’ll find the Madison Station Boulevard Green and Complete Street project. This street was designed to eventually become a walkable, bikeable hub for Madison residents as their neighborhood acquires denser housing, more restaurants and retail options, and entertainment venues.

The concept of green streets gained traction in Nashville in 2016, when Mayor Megan Barry amended the Complete Streets Order to be the Green and Complete Streets Order. Mayor O’Connell reaffirmed the importance of green streets by signing Executive Order 045 in January 2024. The executive order outlines Nashville’s Green and Complete Streets policy and commits Metro Nashville to “encouraging a safe, reliable, efficient, integrated and connected system of Green and Complete Streets that promotes access, mobility and health for all people, regardless of their age, physical ability, or mode of transportation.”

PRIORITIZING GREEN STREETS ALONG THE RIVER

Examples of roads that should be priority green streets include: Davidson Street, Walter S. Davis, Cowan Street, Visco Drive, Opry Mills Drive, and Trinity Lane. Nashville’s rapid growth gives us unique opportunities to design with water quality in mind. In the case of the East Bank, a completely new street will be added to Nashville’s infrastructure.

West Trinity Lane is the next area of proposed development that has the potential to be an example of how smart design can accommodate the growth of a city while protecting the health of our waterways and improving community well-being.

The West Trinity Lane project area.

THE OPPORTUNITY IS NOW: PRIORITIZING TRINITY LANE

Click and drag to navigate around this 360 degree video footage of West Trinity Lane, captured in June of 2025.

West Trinity Lane rolls over steep hills as it glides from the Clarksville Pike bridge to Whites Creek Pike. The topography affords the area some stunning views of the city, but can make implementing green stormwater infrastructure tricky. In areas where the road is too steep for green stormwater infrastructure (typically over 5%), the vision recommends ensuring ample tree canopy is included.

There are several key areas to consider in designing a greener Trinity Lane.

Plan showing how green streets at Clarksville Pike and Trinity Lane could intersect, and highlighting possible greenway connections

Diagram looking northwest at the intersection of Trinity Lane and Clarksville Pike, and showing how greenway connections could be made to Bordeaux

Buena Vista Pike and Clarksville Pike: At the intersection of Buena Vista Pike (which eventually becomes West Trinity Lane) and Clarksville Pike, it is recommended to prioritize canopy trees and multimodal infrastructure that welcomes the community to Bordeaux. Just past the intersection is one of NDOT’s Vision Zero High-Injury Network Priority Projects, so implementing a Green and Complete Street is also crucial for improving safety here. The Clarksville Pike bridge is a vital connection between Downtown Nashville and Bordeaux. Although green stormwater infrastructure like rain gardens may be difficult to implement where the bridge crosses the Cumberland River, robust urban tree canopy along the roadway can unite the green street elements through to North Nashville and downtown.

Diagram illustrating a green street intersection at Trinity Lane and Buena Vista Pike, where new development is planned

Massing model of potential new buildings at Trinity Lane and Buena Vista Pike along the Cumberland River

The Riverside Planned Development: Right now, there is little residential or commercial development along this stretch– but the forthcoming Nashville River District redevelopment presents the opportunity to proactively create infrastructure that can accommodate future land use. The new development will significantly increase the building density along this area, bringing more cars, buses, walkers, and bikers to the road. Implementing a green and complete street along this section of West Trinity and within the Riverside development will be vital.

Diagram showing the view of Trinity Lane and Whites Creek Pike, where the proposed Priority Green Street would begin on the East side of Trinity

Trinity Lane and Whites Creek Pike: This final section of Trinity Lane begins to flatten out and is closer in proximity to residential and commercial development along Whites Creek. Ensuring the green and complete street infrastructure is continued through this intersection will increase safety and improve the water quality near the final segment of the road.

A rendering of a green bus stop that includes plants on the roof and a plants in a rain garden.

Creating a green street along Trinity Lane can also be achieved with transit infrastructure. Bus stops can integrate green roofs and rain gardens to capture additional stormwater runoff and provide bursts of greenery along the road.

CALL TO ACTION

Picture your next trip on a road. Whether by car, bike, bus, or foot, your next journey could be on a green street. Imagining this future is great, but we also need to make it happen. Your voice is valuable to advocate for the expansion of green streets across Nashville– especially right now, when the city has funding for new projects and is actively redesigning the faces of streets like Trinity Lane. Stay in touch with the Cumberland River Compact and the Civic Design Center to find out how you can make your voice heard as these projects develop. And if you haven’t already, you can get out and experience one of Nashville’s existing green streets right now! See you out there!